asc & me

why are you reading this?

The chances are you and I currently, or are about to, spend some time together. Maybe we work together, are living together, or have somehow ended up in each others’ lives. This probably means that at some point you will notice some differences in the way I do things.

This is because I am autistic.

These differences are not inherently bad. Some cause me problems. Some I’m quite fond of. In any case, understanding them can help the time we spend together be easier for both of us.

I’ve written this to help with that understanding. Being autistic, often the words that come out of my mouth don’t match what it is I’m trying to communicate. By writing this down, I hope we can save some time and avoid confusion.

There are two parts to this page. The first explains how I experience autism. I wrote it partially for you, but also partially for me. It is not particularly concise, and I understand if you don’t have the time or energy to read it all. That’s why the second part exists. It is more focused and contains direct suggestions for how we can ensure our interactions are mutually beneficial. If you don’t have much time, go straight there.

sections

a little background

I was diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome1, now called Autistic Spectrum Condition2, at the age of 29. I have been autistic all my life and always will be. This is because autism is a neurodevelopmental condition that affects the way my brain processes information.

You might have heard autism described as a ‘‘spectrum’’. This is because no two autistic people are the same. There are many things we have in common – the traits that make us autistic – but we all experience these in different ways, in different combinations, and to different degrees of intensity.

It’s important to remember that the term ‘‘spectrum’’ does not describe a one-dimensional, linear spectrum, running from less autistic to more autistic. This flawed concept often manifests in the form of ‘‘functioning labels’’. These are terms like ‘‘high-functioning’’ and ‘‘low-functioning’’. I am not particularly fond of these labels, and many other autistic people feel the same way. This is because they reduce the nuance of our experience to a simple assessment of how effectively we conform to neurotypical social norms.

In the short time since I was diagnosed, I have already been called ‘‘high-functioning’’ more times than I can count, mostly by well meaning individuals. Whilst their intentions are usually good, the message this really communicates is, ‘‘you are conforming to several societal expectations, so you can’t be that autistic.’’ This makes it hard to take my own struggles seriously.

The autism spectrum is not one-dimensional and linear.

Instead, it is multidimensional, describing a constellation of autistic traits and characteristics. We are as diverse as allistic3 people. As the saying goes, once you have met one autistic person, you have met one autistic person.

For this reason, it is important to understand that many of the ideas you may already have about autism are very likely based on stereotypes perpetuated by lazy media representations and outdated medical interpretations, centred on a subset of white boys and men. I make this point for three reasons. Firstly, I hope you’ll read what I have written with an open mind, and understand that what I am saying may not perfectly line up with your preconceptions about autistic people. Secondly, I want to be clear that the information I share here is about my experience of autism. Many other experiences are possible and equally as valid. Thirdly, I hope that in reading this you are encouraged to question some of these stereotypes and understand that autism does not end with white cis men.

part 1

but you don’t seem autistic

So I have been told. In fact, I didn’t even know I was autistic for most of my life.

There is a reason for this. You may know already that autism is a condition that affects socialisation and communication. It is commonly assumed that this means autistic people are inherently unable and unwilling to socialise. That we are awkward, verbally clumsy, rude, inappropriate. And some of us are, by neurotypical standards. But some of us aren’t.

Many of us learn to come across as reasonably socially adept, to make friends, to make chit-chat, to hold conversations. We do this through a process we call ‘‘masking’’. This involves suppressing many of our natural instincts, whilst consciously modifying our behaviour to match neurotypical social norms, all whilst remaining hypervigilant to the subtle nonverbal cues that we are often unable to instinctively interpret.

You might think this sounds difficult. You would be right. It is exhausting.

I learned to mask as a teenager. I did it because I was reminded on a daily basis that I didn’t fit in with my peers. From a young age I was socially ostracised. I did not understand why.

The shame of this alienation let me to believe that there was something fundamentally wrong with me. That I had a deficiency. I have yet to speak to another autistic person who didn’t experience this sense of deficiency during their formative years.

This belief led me to take action. I became obsessed with the idea of improving myself, devouring all the information I could on social skills, body language, communication. I perused the internet for tips, making web searches like ‘‘how to make friends’’ and ‘‘why don’t people like me’’. And, I practiced. I would regularly catch a bus to another town, where nobody would recognise me, so I could practice my skills on strangers. To this day, I cringe thinking about some of those encounters.

But, gradually, this effort did begin to pay off. I made friends. In brief, beautiful moments my social anxiety subsided and I felt, for a second, included.

Was that it? Problem solved? Absolutely not. I worked hard, and I am very good at masking. Yet, to this day, for every successful social interaction I have, there is another disaster. And every time that happens, the same shame, the same belief that I am deficient is waiting for me, like it never left.

The thing to understand about masking is that it comes at a cost. Think of it like living in a country where nobody speaks your native language. Of course, you’ll need to learn the local language to survive, but in learning as an adult you’ll likely never reach the fluency of a native speaker. You’ll probably always speak with an accent, miss certain idioms, and need to stay vigilant about grammar. As you speak your internal monologue will be constantly running: ‘‘did I use the right tense? should this verb be in the subjunctive form? should this noun be in the dative or locative case?’’ After every conversation you’ll review it in your head. ‘‘Did I say that right? Oh no, what if I used the wrong form of that verb? They’ll think I was being rude.’’ A few hours at a party, for a native speaker, might be a relaxing way to unwind, but by the end of the night you will probably be exhausted from the effort of simply communicating.

This is how masking feels.

It is a continuous expenditure of cognitive energy for the purposes of conforming to the social expectations of others. And when that energy is depleted life becomes a lot more challenging, and there will be no more masking.

Here is a small selection of the things I have to do to keep the mask up:

- privately rehearse stories, jokes, and conversational set-pieces

- consciously imbue my words with intonation, but not too much as people find this offputting

- question every natural instinct I have to contribute to a conversation – I’m at great risk of infodumping, communicating through facts, or interpreting things literally. People tend not to like these

- mentally keep track of how long each person has been talking so as not to over- or under-contribute to the conversation

- evenly distribute my eye contact between everyone in the group, whilst not staring too long or looking disinterested in anyone

- actively parse for sarcasm, jokes, metaphor. I’m pretty good, but I miss a lot

- suppress my natural movements (called stims)

- suppress my responses to uncomfortable sensory stimuli

sometimes i really like some things

I want to talk about an aspect of being autistic I adore.

Many of us experience something the medical community calls restricted or excessively circumscribed interests. Autistic people often refer to them as special interests. Those around us often call them obsessions or fixations. Sometimes I like to call them fascinations. But let’s not get hung up on terminology.

If you have ever eaten a Pringle or any other delicious, salty, oily snack, you can understand what it is like to have a special interest. Think about the time between one Pringle and the next. That growing, unignorable compulsion you feel to have another is a strangely powerful feeling, no? And when you finally relent there is an undeniable satisfaction, a release. This pattern of dopaminergic4 tension and resolution is almost identical to the feeling of having a special interest. Only, instead of Pringles, we are compelled to consume information and understanding.

Imagine you’re sharing the Pringles with other people. Now you’re under social pressure to suppress your instinct to grab a handful more every time your desire grows. And this only fuels the compulsion, right? By focusing on not instantly grabbing another Pringle, all you can think about is having another Pringle. At some point, you’ll have to relent. Nobody’s willpower is strong enough to withstand this forever. We feel this when it comes to our special interests too. You might have noticed that some of us have a tendency to talk a lot about our current fascination, sometimes launching into lengthy monologues. I can assure you, we are painfully aware. By the time you hear us talking about them out loud, we have already had a lengthy internal battle trying to suppress the urge. Just like when you politely fight your craving for another Pringle.

There is no reason for me to know the etymology of the Georgian word ღვინო. Nor is there any reason for me to know anything about agglutinative morphology, ergativity, or the hypothesised and debunked Altaic language family. Really, no reason. I am not a linguist; I do not work with language in any capacity; I am effectively monolingual, only speaking fragments of two other languages; and my friends roll their eyes when I start talking about this subject.

But I do know about these in what some might see as an excessive amount of detail. You might wonder: why? Why have I compulsively collected information about aspects of linguistics which have no bearing on my day-to-day life? At times, the answer is simply because I am very deeply interested in this subject. It fascinates me. Yet this is just part of the puzzle. My drive to gather, process, and understand this information is not entirely understood scientifically. Various different theories have been proposed to explain why we autistics do this, but none have been empirically validated as a unifying explanation. For this reason, I would like to share a little about the role these intense interests play in my life.

The first is as a sort of emotional and cognitive regulator. As I’m sure will become clear as you continue to read, being autistic can often be stressful, exhausting, and anxiety inducing. Engaging with a fascination, however, is usually the opposite. It produces a sense of calm, of wellbeing, and fulfilment. It is not uncommon to see me reach for my phone in a social setting, but not to check up on social media or respond to messages. Instead I’m likely to be reading about my current special interest. Similarly, there are times when I’m much less likely to be able to contain a verbal essay about the source of my fascination. In a challenging environment – and it’s helpful to understand that what is challenging for me is very often not challenging for allistics – engaging with my interest is soothing and grounding. It can help reduce overwhelm and prevent me from reaching problematic levels of stress.

This is closely related to the second role these interests play. They are a source of consistency. You may have heard that autistic people have an ‘‘insistence on sameness’’. In reality, this varies from autistic person to autistic person, and often manifests differently. At its core, though, for many of us this derives from a need to seek respite from how overwhelming and unpredictable simply existing in the world can be. For me, the knowledge that I can return to my fascination is reassuring, and the act of doing so dissipates the built up anxiety and stress.

Thirdly, fascinations provide an outlet. Think how restless and destructive a young, energetic dog can become when it doesn’t have a chance to go outside to exercise and play. This energy needs to be directed somewhere. Similarly, my brain can become restless and frustrated when it doesn’t have suitable material to engage with, leading me to become anxious, stressed, hyper-analytical, and anti-socially logical. In particular, it craves patterns and problems. This is why I am drawn to mathematics, to computer programming, and to research.

Finally, these fascinations are restorative. We autistic people often experience something called hyperfocus, sometimes pejoritavely referred to as perseveration. This is a trait we share with many people with ADHD. We can become blinkered to the world around us, with all our cognitive energy singularly directed at the object of our focus, to the point that we can neglect to eat, drink, and even sleep. You would be forgiven for wondering how this could be at all restorative. To understand, it is crucial to realise that we spend much of our lives in a state of overwhelm, hovering at the edge of everything becoming too much. Hyperfocus is therefore a sort of momentary sanctuary. A break from our regular experience of bombardment with information.

Some autistic people have one special interest for their whole lives. Some have none. Some cycle between interests. I am in this last group – my interests have lasted anything from days to years. Sometimes when they end, they’re gone forever. Sometimes they come back. Sometimes there is more than one simultaneously.

It is a strange thing losing a special interest. It is entirely involuntary, just like gaining one in the first place. Imagine waking up one day and no longer experiencing hunger. This is how fundamental the drive to pursue them can feel, and so you can picture how disorientating it can be to suddenly be without one. For example, I went from playing chess several hours a day to not thinking about it for months, with no reason why. In many ways I am lucky that I have now found myself on a career path that aligns with a recurring special interest.

A (very) small selection of the special interests I have had:

- linguistics. specifically: phonology, morphology, etymology, and taxonomy, all as singular interests at different times.

- audio synthesis

- computer operating systems

- magic. specifically: mentalism.

- autism itself

infodumping

A friend once quipped, ‘‘if you want a short answer, don’t ask Ben.’’

Everyone laughed.

I laughed too, but I have thought about it daily since then. Because, he was right. If you’re in a hurry, you really shouldn’t ask me. I will provide a comprehensive answer to your question, but it will be long. There will be a lot of extra information you didn’t ask for. We might go on some detours through some tangentially related topics, or I might provide some background. And I’ll probably have to reword things a few times to avoid any misunderstandings.

And oh, I pity you if you made the mistake of asking me about a special interest. We’ll be here for a while.

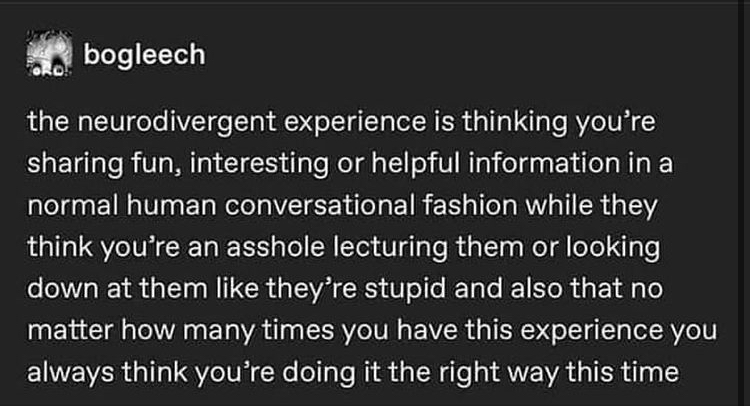

Autistic people refer to this as infodumping: our tendency to overshare large amounts of information, much of it seemingly irrelevant, when it may not be entirely wanted. It’s especially pronounced when we’re talking about something we’re very interested in. We’re sometimes described as ‘‘speaking in paragraphs’’.

Allistic people tend not to enjoy it when we infodump. It can come across as condescending, domineering, arrogant, and many other negative terms that describe something so far removed from the real motivation behind these infodumps that it’s almost funny. Except, in reality it’s usually not funny. It’s not funny to realise only after you’ve finished speaking that you’ve done it again, that everyone is quietly judging, that this may have damaged a friendship. It’s not funny to feel humiliated as the people around you sit in uncomfortable silence once you finish speaking, only for someone to punctuate it with a derisive “anyway…” before changing the topic. It’s not funny to think that for once, finally, you’re doing it right, that someone is genuinely interested in what you have to say, that you’re giving them what they want and connecting with them, only to discover that this is exactly like every other time.

It is, however, slightly funny that when I spend time with my autistic friends, we mostly communicate by infodumping. We speak to each other in paragraphs. In essays, sometimes. We update each other on our special interests, and share mutual enjoyment through this rich, information-dense communication style. It suits us perfectly.

This discrepancy, by the way, is a clear example of what’s known as the double empathy problem: a theory of autistic communication which posits that autistic people aren’t deficient in communication skills and cognitive empathy, but that we instead have a particular autistic style of these. This is why autistic people can typically communicate effectively with other autistic people, just like allistic people have little trouble communicating with other allistics. The challenges arise in autistic-allistic communication, but not because of a deficiency in either group. Just a difference.

So why do I infodump? I believe there are three reasons:

- I am genuinely excited to have the opportunity to speak about this subject.

- I do not know how much information you need in order to understand what I’m trying to communicate.

- I am unable to instinctively read the nonverbal cues that you would like me to stop speaking.

Why don’t I just try not to do it? Trust me, I do try. Very hard. All the time. I am painfully aware of my infodumping, but even with all the cognitive resources I can muster directed at the task of suppressing and avoiding it, I can not entirely prevent it. And, more importantly, even preventing it the amount I already do is utterly exhausting.

I have no doubt that my tendency to infodump is a core reason I have struggled, and still do, socially. I have been unlucky enough to hear second hand some of the things that people, who were once friends, that chose to distance themselves from me have said. Ironically, one of them works with autistic children. Read into that what you will.

the bucket

Now, a short detour from communication to talk about buckets.

You have a bucket. I have a bucket.

Your bucket is bigger than mine. And your bucket has a hefty spigot that drains the water effectively. My bucket has a small, flimsy tap that, even fully opened, emits only a gentle trickle.

You start the day with an empty bucket. I start with some water in mine.

You are in the kitchen making coffee, and you spill some on the floor. ‘‘Shit,’’ you say, as you look for the dustpan and brush to sweep them up. This stressed you out a little. A small amount of water is added to your bucket. My morning starts the same way. This stresses me out too and the same amount of water is added to my bucket.

You head upstairs to take a shower. Oh, but there’s someone in the bathroom. No worries, you head to another room and do something else while you wait. Your bucket stays the same. The same happens to me, but this isn’t how I planned my morning. I was supposed to shower at 8:30. If I don’t shower now then I won’t have time to make the breakfast I planned before I have to leave the house. And if I make it before I shower I would have to eat it cold afterwards. I am stressed out by this. I have to adapt my plan on the fly and this is difficult for me. A small amount of water is added to my bucket.

As I try to think about how to proceed with my broken morning plan, I am unable to ignore the sound of my neighbours having a conversation through the wall. This sound is accompanied by the buzzing of a ceiling light’s dimmer switch, and punctuated with two dogs in adjacent gardens across the street barking to each other. It is all I can focus on, and the sounds feel unpleasant, intrusive, and unwelcome. I can’t tune them out. As you might expect, more water is added to my bucket.

We are minutes into the day, and my bucket has had three times more water added to it than yours. What’s more, my bucket started with water in it, and is smaller than yours overall. Do you see where this is going?

Let’s jump five or six hours into the future. It’s the afternoon, and let’s imagine both our days have been moderately stressful. Water has been added to your bucket, and water has been added to mine. But more has been added to my bucket. Why? Because many of the moments that are inconsequential to you are a challenge to me.

Let’s look at an example. In the middle of the afternoon, we both take a break from work to go meet a friend for coffee. You are happy to see your friend. They tell you about their holiday. You tell them about what you did on the weekend. You laugh effortlessly together and leave feeling relaxed. While you were there, the tap on your bucket was opened, and the water drained out. Is this always the case? Of course not. But much of the time it is.

When I meet my friend, we sit in a café. It’s noisy and there are a lot of people moving around and I can’t help but notice how sub-optimal the seating arrangement is. We’ve sat at a table meant for four people, because it was all that was available when we arrived, and now a couple is leaving their small table and a group of five are gathering chairs from around the café to turn it into an honorary table-for-five. I want to suggest we swap tables with them, but they’re on the other side of the café, and the thought of approaching a group of 5 people who have just put so much effort into moving chairs to suggest they move the chairs back and change seats is anxiety inducing. My friend has just asked me a question but I have no idea what they were talking about. I ask them to repeat themself and I think I detect a glimmer of annoyance on their face. That’s what flared nostrils, neutral mouth, and a sharp inhale/exhale means right? As they start speaking again a woman at the next table laughs loudly and it’s piercing. My reflex is to wince but I know my friend will misinterpret this as directed at them so I try to suppress it and I realise I’m not listening again. Okay, pay attention. I realise they’re asking if I know a particular person. ‘‘Yes,’’ I say. That woman had a strange laugh. It started with a weird raspy noise. It replays in my head as if she’s still laughing. I wonder if there’s a phonological name for that sound. Like white noise passed through a very resonant filter. Some sort of aspirant? A glottal fricative? Maybe if I excuse myself to the toilet I can look it up. ‘‘And?’’ my friend says. I suppose I must look confused, because they continue. ‘‘Where did you meet her?’’ I realise I’ve answered the question too directly. Focus. Let’s give some extra information.

My friend looks vexed as I trail off without a point. I expect I spoke for about a minute continuously. That was probably too much. ‘‘Right, well anyway,’’ they continue. I am happy to see my friend. I like them and they are interesting. But it is not easy to do so. Throughout this visit, water was added to my bucket several times. For brief moments, the tap was opened, but as you may remember my tap is far less effective than yours. I leave the cafe with my bucket nearly full. You leave with yours nearly empty.

Everyone has a bucket. Everyone’s bucket is different. Some are big, some are small. Some have big taps that open easily, whilst some have small taps that barely let the water escape. Autistic people tend to have small buckets, and this alone is difficult.

But the big difference between your bucket and mine, is that many things that remove water from your bucket, or do nothing to it, can add water to mine.

Naturally, you might be wondering, what happens when the bucket gets full?

shutdowns

communication styles

You see, I tend to amass information.

nonverbal communication

sensory input

executive dysfunction

part 2

troubleshooting

-

this name is now considered problematic for a number of valid reasons. I don’t mind it being used to describe me, but out of respect for the wider autism community I tend to simply describe myself as autistic. ↩

-

this term is preferred by many autistic people in lieu of the accepted medical name Autism Spectrum Disorder. ↩

-

a word adopted by the autism community to describe someone who is not autistic. This is a distinct term from ‘‘neurotypical’’, which describes someone not affected by the many conditions collectively referred to as neurodivergent. ↩

-

there is a growing body of evidence that serotonin and dopamine pathways in autistic individuals function differently from those in allistics. ↩